This policy brief was originally published in Japanese as part of a series of papers produced by a joint research project conducted by the Japan Center for International Exchange (JCIE) and the Tokyo University Institute for Future Initiatives (IFI) to provide analyses on global and regional health governance systems and structures and to offer concrete recommendations about the role Japan should play in the field of global health.

Overview of existing financing mechanisms for health security

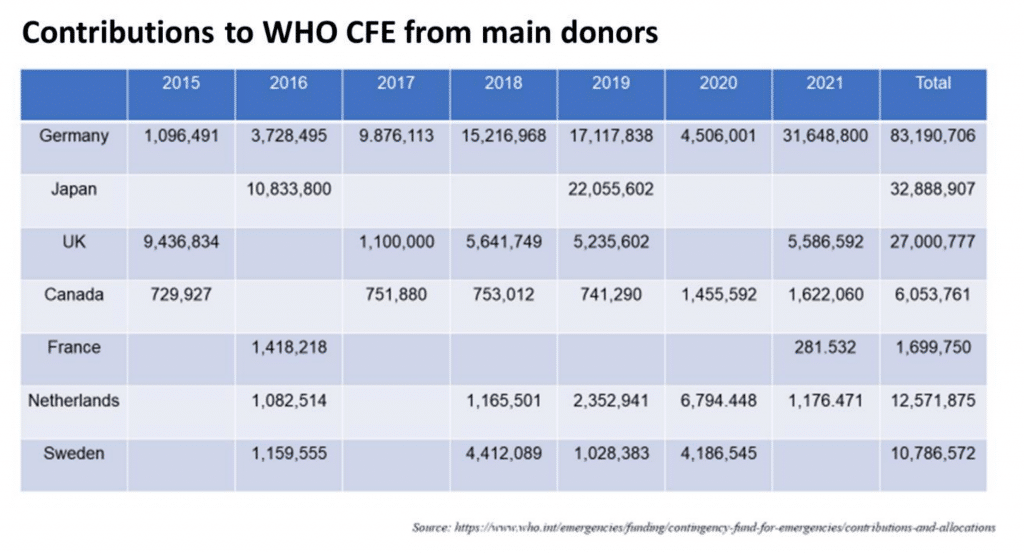

When a health crisis emerges, the speed of the response in the early stages to prevent the crisis from further spreading is extremely important. But to do so, there must be a flexible and agile allocation of sufficient funding to WHO and other organizations that handle crisis management. Various funding mechanisms for health security have been established to date, especially after the 2013 Ebola outbreak in West Africa. The most representative is the WHO Contingency Fund for Emergencies (CFE),1 which was established in 2015 for the purpose of enabling a swift response. Contributions from donor countries to the CFE are collected and pooled in advance so that the funds can be immediately allocated when an actual health emergency breaks out. There is usually a time lag between the outbreak of a health crisis and the time the funding arrives from donors, but this lag time is expected to be minimized by allocating funding that was contributed and pooled in advance. The following shows contributions to the CFE since it was established in 2015. Japan’s contributions in 2016 and 2019 make it one of the main donors.

Likewise, another funding mechanism that relies mostly on contributions from donors is the United Nations Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF).2 CERF is a mechanism established to allocate funds to UN humanitarian agencies for two objectives: 1) rapid response—covering the initial resources necessary for emergency humanitarian aid when a large-scale disaster or conflict strikes in order to contain damage to the minimum level; and 2) underfunded emergencies—supporting humanitarian response activities within an underfunded humanitarian emergency (so-called “forgotten crises”). The secretariat is located within the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). There is a similar fund called the Country Based Pooled Fund (CBPF),3 which allows donors to pool their contributions into single, unearmarked funds to deliver timely assistance when a new humanitarian crisis arises, or when an existing emergency significantly deteriorates. And finally, another major funding mechanism is the Pandemic Emergency Financing Facility (PEF), housed at the World Bank.4 Although this mechanism has already been closed, it was one of the key funding mechanisms at the initial stage of COVID-19. The PEF was launched in 2017 to rapidly and smoothly mobilize funding to help prevent disease outbreaks from becoming pandemics. To do so, the World Bank conducts derivative transactions with insurance companies and issues pandemic bonds for investors. In contrast to conventional funding mechanisms like the CFE and CERF that rely on contribution from donors, the PEF was highly anticipated as an innovative insurance-based mechanism to draw in money from the capital market to help respond to health emergency outbreaks.

The limits of the CFE, PEF, and other mechanisms in responding to COVID-19

Like many other health crises, a large amount of funding was required to fight the COVID-19 pandemic that suddenly emerged toward the end of 2019, and a certain level of funding was allocated from the mechanisms described above. For example, the CFE allocated US$13 million,5 while the CERF and CBPF allocated a total of US$490 million (CBPF US$250 million + CERF US$241 million).6 In addition, World Bank’s PEF funded a total of US$195.8 million (as of April 2021 for PEF and as of February 2022 for all the other mechanisms).7 These figures demonstrate that existing funding mechanisms played a substantial role in fighting the crisis, but when a global pandemic of the size of the COVID-19 strikes, the available funding is far from sufficient. At the same time, this experience also revealed the various challenges facing the existing mechanisms.

For example, mechanisms such as the CERF, CBPF, and CFE pool contributions from donors in advance so that they can immediately release their funds to ensure rapid response when actual health crises occur, but because they are completely reliant on donors and their contributions, the amount of funding they can secure is small (this is especially true for the WHO’s CFE). Moreover, when a crisis becomes protracted, as in the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, funds start to deplete and the WHO itself must put a great deal of effort into fundraising. In principle, however, it is much more desirable to have a system in place where funding rapidly flows into the WHO when a global health crisis strikes, so that the WHO will not have to expend time on fundraising but rather can devote its full capacity to the crisis response. In light of the mission of the CFE, which is to focus exclusively on the initial response (the CFE funds are to be used within the first three months after the onset of an emergency, in principle), it is not appropriate to turn to the CFE to handle a protracted health crisis that grows more serious as time passes, as has been the case with COVID-19. As is the case with many mechanisms that rely on contributions from donors, it has been noted that while rapid and flexible funding is desirable in responding to a crisis, many donors prefer to earmark their contributions, and therefore detailed coordination with the donors is required before and after the funding is used. Some also point out that while there are other departments within the WHO (such as the WHO Emergency Programme) with budgets that can be used for health crisis response, the budgets of different internal departments were not appropriately coordinated.8

With regard to the PEF, the length of time required before funding is disbursed and the rigidity of the activation criteria have been raised as issues. For example, during the 2018 outbreak of the Ebola virus in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), which resulted in over 2,000 deaths, the PEF could not be activated because the outbreak did not satisfy the criteria of more than 20 fatalities in two countries other than the DRC. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the PEF was not activated until April 17, 2020, three months after the first patient was reported in China in December 2019. This was because the PEF required that “at least 12 weeks had passed from the start of the outbreak” in addition to other criteria on “the rolling (or ongoing) total case amount.” There is a contradiction here: despite the fact that a rapid initial response is critical to health security, the PEF cannot mobilize funds until the pandemic has already progressed to a certain extent. Although this may be a rather technical issue, depending on the pathogen, infectious diseases are diverse in terms of their pathology and impact, transmission routes, rate of severe cases, fatality rate, and speed of spread. Therefore, triggers that were put in place with an infection like Ebola in mind may be inappropriate for COVID-19 or other diseases. This is quite different from responding to natural disasters in which the damage is relatively easier to assume. Another difference is that, in the case of natural disasters, the damage is basically greatest at the outset and does not rapidly spread with time. In the case of infections, however, as was seen in the case of COVID-19, the overall picture of the damage is hard to grasp in the initial phase of the outbreak, and waves of the pandemic recur in a cycle of every several months, making it very difficult to design an insurance product.

Challenges of existing mechanisms revealed by the COVID-19 pandemic

The sections above have looked at existing funding mechanisms for health security, mainly focusing on the CFE and PEF, but a more fundamental issue should also be noted: the definition of “funding necessary for health security” has not yet been clearly defined. The term “health security” is very broad and vague, and as a result, the overall picture of the total amount of funds needed to respond to health crises, the amount of contributions from donors, and the funding gaps that have arisen remain unclear. In other words, the transparency of funding is not ensured, and in fact, countries affected by health crises are experiencing inefficiencies such as shortages or duplication of funding. Funding inefficiencies in emergency situations impose an unnecessary burden on both the donor and recipient countries, making it difficult to achieve the outcomes that could otherwise have been realized, and moreover, the tendency for contributions to concentrate on areas that are easy for donors to understand can lead to funding shortages in more complex but necessary areas such as highly specialized or innovative techniques.9

As noted above, the WHO’s CFE was unable to adequately fulfill its role during the COVID-19 pandemic, but that of course does not mean that the CFE is unnecessary. Since the CFE was established in 2016, it has rapidly and effectively funded initial responses to a number of local outbreaks in low- to middle-income countries, helping to contain the spread of such outbreaks, and the CFE will continue to be useful for responding to local outbreaks in low-to-middle-income countries as was originally envisaged. However, in order to fight a global pandemic that is on a completely different scale in terms of the damage it inflects, like the current COVID-19 pandemic, we will need to go back to square one and devise an entirely new mechanism. The conventional funding mechanisms that rely on donor contributions is clearly not enough and we will need to dramatically increase the overall scale of funding by drawing on private funds. In that sense, we have a lot to learn from the experiences of the PEF, which is a mechanism designed to promptly mobilize working capital. Although PEF has already closed on April 2021, the outcomes and lessons should continue to be examined.

From the viewpoint of the rapid mobilization of market funds, another initiative of note was the COVID-19 Solidarity Response Fund, which was established under the leadership of WHO Director General Dr. Tedros Adhanom to fight the current COVID-19 pandemic.10 This was a fund to collect donations widely not only from WHO member states but also from private organizations and individuals, and it marks the first time that the WHO has called for donations from individuals. The Solidarity Fund has succeeded in raising more than US$256 million in total. However, the Solidarity Fund is basically a mechanism to raise funds through donations, and as the COVID-19 pandemic stretches on, the pace of fundraising is slowing down. To achieve the necessary magnitude and speed of funding and flexibility of spending, we need to explore new funding mechanisms that do not rely solely on donor contributions.

About the Author

Haruka Sakamoto is an Associate Professor in the Department of Hygiene and Public Health at Tokyo Women’s Medical University.

Notes

- For more on the CFE, see https://www.who.int/emergencies/funding/contingency-fund-for-emergencies.

- For more on CERF, see https://cerf.un.org/.

- For more on the CBPF, see https://www.unocha.org/our-work/humanitarian-financing/country-based-pooled-funds-cbpf

- For more on the World Ban’s PEF, seehttps://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/pandemics/brief/pandemic-emergencyfinancing-facility.

- https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/documents/emergencies/cfe-allocations-2015-2022- feb22.pdf?sfvrsn=716ec302_5 (Only the total of CFE allocations whose purpose was described as response to “COVID-19” or “Novel Coronavirus” as of end of February 2022)

- https://data.humdata.org/dataset/cerf-covid-19-allocations

- https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/pandemics/brief/fact-sheet-pandemic-emergency-financing-facility

- Jain V, Duse A, Bausch DG. Planning for large epidemics and pandemics: challenges from a policy perspective. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2018;31(4):316–24; Lawson ML. Foreign aid: international donor coordination of development assistance. 2013.

- Vageesh Jain, “Financing Global Health Emergency Response: Outbreaks, Not Agencies,” Journal of Public Health Policy 41, no. 2 (2020): 196–205.

- https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/donate