This policy brief was originally published in Japanese as part of a series of papers produced by a joint research project conducted by the Japan Center for International Exchange (JCIE) and the Tokyo University Institute for Future Initiatives (IFI) to provide analyses on global and regional health governance systems and structures and to offer concrete recommendations about the role Japan should play in the field of global health.

The COVID-19 pandemic that has been sweeping the world since 2020 has renewed our awareness that when faced with a global health threat, the international community must unite its efforts to respond, and that governments must take a whole-of-society approach both domestically and internationally. The pandemic has been recognized as a public health and healthcare emergency in many countries, and while various measures were introduced under the leadership of governments, the implementation of those measures has involved the active participation of not only government agencies but a variety of civil society actors, including for-profit businesses, private medical institutions, academic and research institutions, and nongovernmental organizations.

In the global health field, strengthening public-private partnership and cooperation with civil society has long been considered integral to the attainment of the sustainable development goals (SDGs) and universal health coverage (UHC). However, the significance and effectiveness of such cooperation are not necessarily understood by all stakeholders. This is partly because the meanings of such words as “civil society” or “non-state actors”—those groups that are supposed to be collaborative partners—have been vaguely defined by each subsector of health, depending on the actors with whom they have traditionally partnered. The diverse actors that can be categorized as “non-state” hold different positions and specific interests, while there is no formal mechanism to steer them together nor an open process to form a common understanding. This policy brief examines the significance and challenges of public-private partnership in global health and explores multistakeholder relationships for effective global health cooperation in the post-COVID era.

Civil society engagement in the global health sector

In recent years, engagement and collaboration with non-state actors, particularly with civil society actors, have been expanding in global health governance and program implementation. The significance and importance of such engagement are widely recognized by international organizations in the health sector, including the World Health Organization (WHO).1 The HIV/AIDS activism that began in the 1980s contributed to expanding the participation of affected communities in the delivery of health services and public health administration. That formed the basis for civil society organizations to play more significant roles in various global health issues— from policymaking to offering tailored healthcare services, providing patient-centered inputs for setting norms, and monitoring health services. In the 2000s, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (hereafter, Global Fund) and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance (hereafter, Gavi) were founded as new public-private partnership organizations to maximize the impact of global health responses, which led to the recognition of the important roles of civil society and public-private collaboration in public health. It also helped normalize the meaningful engagement of civil society and non-state actors in global health governance in order to maximize the effectiveness of external assistance in the health sector. Because the Global Fund and Gavi require multi-constituency coordination mechanisms on the national level as a condition to accessing grants, the recipient countries have come to engage both the public and private sectors in decision-making discussions, an in fact, for quite some time now, multistakeholder discussions and approvals have become the standard for health policymaking on the national level. These moves were in line with the suggestions of a 2004 UN report that urged all partners to address various social issues through more continuous and effective multistakeholder partnerships with non-state actors and civil society rather than just incorporating the perspectives and capacities of various stakeholders on an occasional or “as needed” basis.2

Even if the participation of civil society and non-state actors in global health governance has become the norm, it is still unclear which organizations and entities make the best participants. The WHO Framework of Engagement with Non-State Actors,3 published in 2016, defines non-state actors as “NGOs, private sector entities, philanthropic foundations, and academic institutions”; these are quite literally relevant entities that are not state governments. Each organization has its own interests, aims, capabilities, and experiences, and even if such non-state actors in general are invited to engage in governance, there is no standard as to which nonstate actor should act on that opportunity or on whose behalf they should participate. It has also been noted that even in international health organizations and partnerships advocating for public-private partnerships, the nonstate actors representing civil society in their governing boards are often academic institutions, medical professional associations, and industry representatives,4 who are not necessarily in the position to represent or reflect the voices of citizens or grassroot organizations. As limited as the participation may be, however, the fact that representatives of the civil society are at least in the room where decisions are made may have the effect of deterring the donor or recipient governments from adopting policies that are convenient only for themselves. It may also prevent excessive political intervention into the discussion, while it also increases the transparency of decision making, and contributes to enhanced accountability.

Significance of public-private partnership organizations

For global health-oriented international organizations that are public in nature, the nonstate actors they work with in public-private partnerships—in other words, the “private” counterparts—play various roles. They can be the funders, program implementers, technical advisors and partners, beneficiaries, watchdogs, or lobby groups, but most of all they are recognized as a variety of indispensable partners in the effort to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages. Especially since 2015, when the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were adopted, public-private partnerships have become the framework of choice to embody the SDG spirit of “leaving no one behind.” To achieve UHC, health services must be delivered to those people who remain unreached by public services, and there is a growing expectation that civil society and nonstate actors can effectively provide last-mile delivery of such services.

NGOs and civil society play a special role in the health sector, particularly when the recipient country’s government cannot fulfill its responsibility to provide health services and meet the level of accountability required by bilateral or multilateral assistance programs. In countries and regions suffering from natural disasters, infectious disease outbreaks, conflicts, or weak state governance, NGOs and other civil society entities are expected to assume the role of the beneficiary partner of international cooperation as a “relatively more effective” agent to deliver health services. Experiences not only in humanitarian aid but in response to the recent COVID-19 pandemic have added evidence that strengthening public-private partnership in peacetime can help improve readiness for emergencies and provide a necessary safety net for citizens.

Public-private partnership in the post-COVID era—learning from the examples of the Global Fund and Gavi

Public-private partnerships in the global health sector have been expanding since the early 2000s, and after two decades, that collaboration is becoming even stronger. Public-private partnership is no longer just a gesture that pays lip service to civil society or a goal to strive toward in international cooperation or assistance methods, but rather it is a necessary framework to achieve maximum impact when investing in health. To better understand the current status and future prospects of public-private partnerships, we will now turn to on two representative examples, the Global Fund and the Gavi.

The public-private partnership of the Global Fund

The Global Fund was established in 2002 as a public-private partnership organization and since its creation it has consistently worked to engage closely with the civil society and private sector and to strengthen ties with the affected communities. Most notably, from the very beginning, 5 out of 20 voting seats on the Board of the Global Fund have been allocated to nonstate actors, of which 3 are held by civil society representatives.5 These representatives have achieved concrete results and have a strong influence on organizational governance, including the mainstreaming of human rights and gender, as well as community engagement. They have also advocated to ensure that success is measured not just by quantifiable outcomes such as the “number of lives saved” and “value for money,” but by qualitative outcomes such as how the Global Fund’s support contributes to solving various peripheral social issues as well. At the country level, the Global Fund strongly recommends that the beneficiary countries meaningfully engage NGOs and the affected communities in the implementation of programs it supports. It also requires that a wide range of representatives from both public and private sectors be part of the Country Coordinating Mechanism (CCM), the national body that is responsible for creating the Funding Requests, coordinating, and overseeing implementation to ensure transparency in terms of how the funding is used. While the participation of representatives of civil society organizations and beneficiary communities was often a token gesture at first, with capacity-building support from the Global Fund, they have developed into full-fledged partners in the governance and implementation of the projects at the country level.

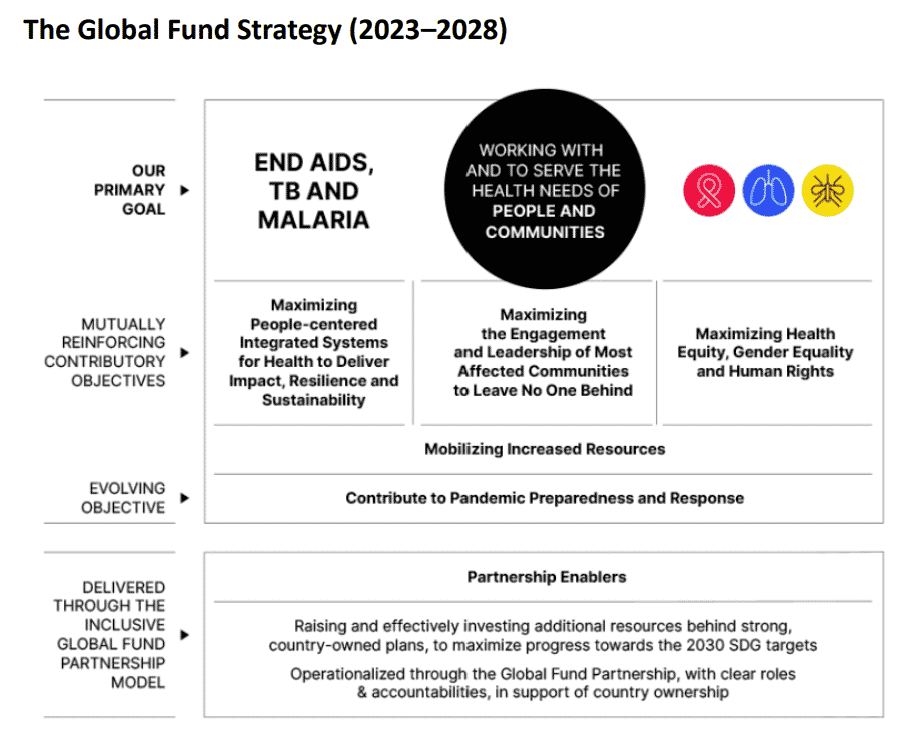

As shown in the figure below, the latest Global Fund Strategy (2023–2028)6 also views collaboration with people and communities as being essential to achieve the primary goal of ending the epidemic of HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria, and considers closer engagement with civil society as a prerequisite. The fact that the strategy includes “maximizing the engagement and leadership of most affected communities” as one of three “mutually reinforcing contributory objectives” indicates that maximizing impact through strengthened public-private collaboration has become a strategy of choice.

The Gavi public-private partnership

Gavi was also established as a public-private partnership, and since its foundation, the Gavi has had strong relations with medical professional associations and pharmaceutical companies as nonstate governance partners. Engagement with NGOs and community groups closer to the beneficiaries was limited compared to the Global Fund. This is partially because the routine immunization programs that Gavi supports at the country level are delivered primarily by the government or public maternal and child health services. Engagement with maternal and child health NGOs and community groups has been limited to cooperation in grassroots advocacy for health education and better understanding of vaccinations. Since the UN’s adoption of the SDGs, and particularly in Gavi’s new five-year strategy (Gavi5.0) for the period of 2021–2025, Gavi laid out the objective of immunizing all children, and setting its primary goal as decreasing the number of unvaccinated (“zero-dose”) children in particular, and it expressed its willingness to strengthen collaboration with nonstate actors and civil society to ensure equitable access to vaccines. In 2021, it launched the Civil Society and Community Engagement (CSCE) Strategic Initiative to create an “enabling environment for effective and sustainable engagement” of civil society organizations (CSOs), aiming to enhance CSO engagement in advocacy and effective program implementation.7 One of the pillars of this Strategic Initiative is to enhance the capacity of CSOs that have not actively engaged in immunization programs in the past to support their increased access to global and countrylevel Gavi funding mechanisms. This shows the Gavi’s heightened expectations for nonstate actors and the civil society as strategic partners. Under the current strategic initiative, a portion of the technical assistance funds will be allocated to enhancing CSO capacity in beneficiary countries, showing their desire to help develop implementing partners who are also technically reliable.

Both the Global Fund and the Gavi are funding agencies that do not have offices or staff stationed in the beneficiary countries. In that context, civil society provides a valuable thirdparty perspective to observe and monitor the implementation of programs by the state government. This watchdog role has been especially important during the COVID-19 pandemic as secretariat staff could not visit the implementing countries for on-site monitoring due to travel restrictions and was also effective for timely understanding of how the COVID19 response measures were impeding the progress of program implementation and the negative consequences thereof. It is essential that the monitoring capacity of civil society and vulnerable communities be strengthened in order to improve preparedness for future pandemics.

Public-private partnership in the post-COVID-19 era

As described above, public-private partnership in the global health sector and strengthening collaboration with nonstate actors have become “strategically integral” to achieving UHC and “leaving no one behind.” The ACT-Accelerator was quickly established in 2020 as an international system for public-private collaboration in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, but here too, it was existing public-private partnerships in the health field that played a central role along with governments, businesses, and various nonstate actors. 8 The so-called vaccine nationalism and vaccine diplomacy seen in many high-income countries have impeded the equitable global allocation of limited vaccine supplies. Yet in order to resolve such issues, it is essential to create stronger frameworks for eliminating inequity through more effective public-private partnerships and the participation of civil society, thereby mitigating the influence of donor governments’ wishes or the pursuit of profit by businesses. At the same time, the COVID-19 pandemic has further highlighted the differences in the influence and interests of the various groups that are considered to be nonstate actors—from groups rooted in communities vulnerable to infectious diseases to medical professional associations and that private corporations (like pharmaceutical companies) with which governments are competing to partner. Therefore, the wide-ranging, vague, and potentially comprehensive collaboration frameworks called “public-private partnerships” should be reconsidered in the context of both governance and implementation to define more clearly who should represent what position. Likewise, for any organization in the health sector, it is necessary to review and update engagement and collaboration with civil society to maintain a perspective that more closely reflects the interests of the beneficiaries. Strategic and mutually complementary public-private partnership in the field of global health still needs to be further strengthened. It is expected that such partnerships will become increasingly diverse in their directions and that concrete collaboration will produce visible improvements in health indicators.

About the Author

Motoko Seko is an Associate Professor at the Dept. of Social System Design at Eikei University of Hiroshima, and a Member of the Technical Review Panel of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria

Notes

- WHO, Framework of Engagement with Non-state Actors (FENSA) (adopted at the 69th World Health Assembly, May 28, 2016 A69/10), http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA69/A69_R10-en.pdf.

- United Nations, We the Peoples: Civil Society, the United Nations and Global Governance (report of the Panel of Eminent Persons on United Nations—Civil Society Relations, United Nations 58th Session, 2004), A/58/817.

- WHO, FENSA.

- K. T. Storeng and A.B. Puyvallee, “Civil Society Participation in Global Public Private Partnerships for Health,” Health Policy and Planning no. 33 (2018): 928–36.

- Civil society representatives hold three seats: one seat represents nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) from the developed world, one represents NGOs from the developing world, and the third seat represents communities most affected by the three diseases. Other non-state actors hold additional two seats, namely representatives of private foundations and private sectors.

- The Global Fund, Fighting Pandemics and Building a Healthier and More Equitable World: Global Fund Strategy 2023–2028 (Geneva: Global Fund, 2021).

- Gavi, “Gavi Civil Society and Community Engagement Approach” (Appendix to a 2021 report to the board), https://www.gavi.org/sites/default/files/board/minutes/2021/23- june/08%20-%20Annex%20A%20-%20CSCE%20Approach.pdf

- Dalberg Advisors, ACT-Accelerator Strategic Review—An Independent Report Prepared by Dalberg (8 October 2021), WHO website, https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/act-accelerator-strategic-review.