This policy brief series is the product of a joint research project conducted by the Japan Center for International Exchange (JCIE) and the Tokyo University Institute for Future Initiatives (IFI) to provide analyses on global and regional health governance systems and structures and to offer concrete recommendations about the role Japan should play in the field of global health.

Introduction

In January 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared that the global outbreak of the novel coronavirus disease known as COVID-19 constituted a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC). A Statement on COVID-19 issued at an Extraordinary G20 Leaders’ Summit held virtually in March of the same year reaffirmed the need for quick action through international cooperation. In response, the WHO and a group of partners, initially including international organizations active in the health field, the European Union (EU), France, and private foundations, launched the Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator (ACTA) on April 24, 2020. The objective of ACT-A is to accelerate the development and production of COVID-19 tools and to create a framework to ensure fair and equitable access and distribution of such products. ACT-A comprises four pillars—Vaccines, Therapeutics, Diagnostics, and the Health Systems & Response Connector (HSRC, initially called the Health Systems Connector)—of which the Vaccine pillar is also known as COVAX (short for COVID19 Vaccines Global Access), with WHO acting as the global coordinator and bearing the responsibility of access and allocation.1

The ACT-Accelerator Strategic Review, an ACT-A interim review report (hereafter, Strategic Review) was published in October 2021. The Strategic Review recognizes the positive achievements of ACT-A in accelerating the development, supply, and access to COVID-19 tools and recommends that, although it is a time-limited collaboration, ACT-A should continue its activities until at least the end of 2022. On the other hand, it analyzes the current situation by sorting the various challenges faced by ACT-A that have impeded the achievement of its objectives into the categories of external and internal challenges.2 The Strategic Review did not analyze in detail some factors identified as “external challenges” and some elements deemed outside the scope of the essential mandate of the Health Systems (& Response) Connector. I will therefore focus on these factors in this policy brief and will emphasize that in order to ensure fair and equitable access to healthcare, including access to medical tools, it is essential to have continued and consistent efforts at all levels, from grassroots to global policies, to close the gap through inclusive, democratic, and transparent decision making.

Achievements and challenges of ACT-A

(1) Disparities in access to vaccines, diagnostics, and therapeutics

Among the four pillars of ACT-A, COVAX did not function as initially hoped. This was partly because of the rise of vaccine nationalism, where high-income countries pursued bilateral contracts with vaccine manufacturers to secure priority access to vaccines and hog more than their share, leaving insufficient supply for COVAX. One thing that needs to be noted here is that the lessons learned from the 2009 influenza A H1N1 pandemic were not heeded.3 At the same time, an increasing number of higher-income countries have donated vaccine doses to low- and middle-income countries out of their excess domestic supply during this pandemic, but because the donations were not always well planned and various challenges arose, COVAX and its partners, AVAT and Africa CDC, were compelled to issue a joint statement calling on the international community to adhere to certain standards when donating vaccines.4 In terms of diagnostics as well, there are wide disparities among countries depending on their income levels.5 The slow pace of approval of test kits for inclusion on the WHO’s Emergency Use Listing (EUL) and insufficient technical support have been cited as key bottlenecks.6 It is estimated that six out of seven infected persons in Africa are undetected,7 and there is an urgent need to disseminate affordable rapid antigen tests that do not require sophisticated equipment.8 With regard to therapeutics, there is no clearly articulated joint procurement structure yet to supply countries or to negotiate contracts nor an Advance Market Commitments (AMC) mechanism for low-income countries, which puts therapeutics at risk of being hogged by higher-income countries, as was in the case of vaccines.9 Merck entered into a license agreement with the Medicines Patent Pool (MPP) for the manufacture of antiviral drug, Molnupiravir. It is therefore thought that most of the demand for the drug from lowerincome countries can be covered by generic drugs.10 However, there have been complaints that some of the upper middle-income countries experiencing severe outbreaks of COVID-19 are not covered by the MPP, and the voluntary licensing agreement between MPP and Merck includes a termination-upon-challenge clause.11

(2) Perception of the health system

The Strategic Review noted that limited coordination between the WHO’s Health Emergencies Programme (WHE) and the HSC led to missed opportunities for ACT-A. Responding to this point, ACT-A announced in its Strategic Plan & Budget (October 2021 to September 2022) that the HSRC would fully integrate the WHE and UNICEF into the work of the revamped “Health Systems & Response Connector.”12

Meanwhile, there were fundamental debates over the health systems pillar mandate that went beyond just the need to ensure collaboration among individual organizations. The Strategic Review notes that there was ambiguity over whether the HSC should play a humanitarian assistance role (along the lines of emergency assistance in times of disaster) or one of medium- to long-term social development, and different institutions had very different perspectives on the HSC’s goals. The Strategic Review takes the position that ACT-A’s mandate is “ending the acute phase of the pandemic,” and any work that would require a longterm perspective, such as building a stronger system to prepare for the next pandemic, is not within the mandate of ACT-A and should be carried out by a separate entity.13 This seems to be an extension of the idea of “equitable allocation of tools” and seems to view health systems as a means to that end. On the other hand, the Platform for ACT-A Civil Society & Community Representatives, a platform for civil society organizations (CSOs), has released statements requesting that the activities of the HSC/HSRC be centered on healthcare human resources rather than on the procurement of personal protective equipment.14 This request seems to take the position that mid- to long-term issues, including securing healthcare human resources, are integral to and inseparable from robust health systems as the prerequisite for the deployment of healthcare tools.

(3) Transparent and democratic governance and decision making

The Strategic Review points out that nearly two-thirds of the current member states of the Facilitation Council, a body responsible for the overall governance of ACT-A, are categorized as high-income countries, and the voices of lower-income countries may not be sufficiently represented. Also, those member states that are also members of existing governance structures of international organizations can exercise influence through other channels. Those facts and others raise the concern that decisions are sometimes made at times through processes that lack transparency, and that the voices of CSOs and community representatives (CRs) are not adequately reflected.15 The structure of ACT-A has been changing as new partners have joined as the collaboration proceeds. Although representatives from the pharmaceutical industry remain listed as part of the Principals Group, their corporate logos no longer appear in the organizational chart, making them less visible in the collaboration. As seen in this example, some stakeholders point out that the presentation of information is inconsistent and that accountability throughout ACT-A is unclear.16 While it should be appreciated that nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and CSOs are participating to a certain extent in the governance of ACT-A and its constituent organizations, they do not necessarily have a great deal of influence, and there is some ambiguity regarding their representativeness. 17 There is also room for improvement in terms of the gender gap in the representation of men and women in governing bodies.18 Who participates in decision making under what mechanisms is an important point when examining what potential bias could affect that decision making. Specific measures must be implemented to reform ACT-A from the viewpoints of promoting participation of those people who are most vulnerable to the impact of the pandemic, providing support to areas that are often neglected, and transparency of information in democratic decision making.

(4) Transmission of information and imbalances in funding

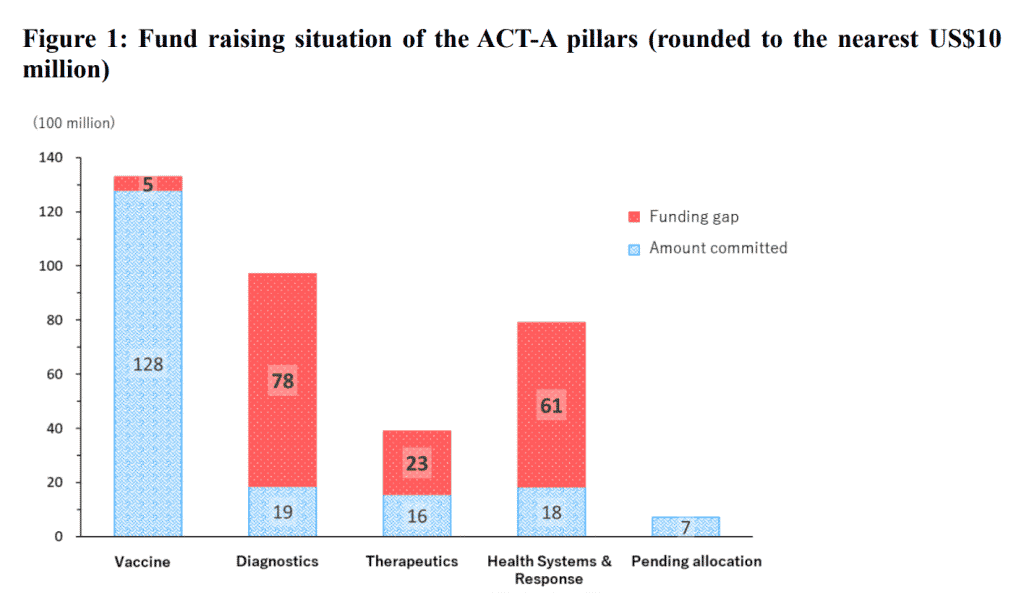

Although ACT-A does make some effort to disclose information, such as indicating its overall funding needs19 and publishing its progress online in a consolidated manner,20 there has been criticism that the full picture of ACT-A’s specific funding flows is difficult to capture.21 In part because of this limited visibility of the aggregate financial flows, pillars other than the vaccine pillar, which attracts the greatest attention from donors, are suffering from chronic funding shortage (fig. 1). ACT-A needs to develop a more effective communication strategy to attract adequate funding for all areas as needed. In doing so, it is important from the perspective of fair and equitable access to provide detailed and convincing explanations about those areas in which higher-income countries (who are the primary donors) are not as interested and to incorporate a grassroots-level viewpoint that incorporates the perspective of vulnerable people.

Primary healthcare as the foundation of fair and equitable access to healthcare, including in response to pandemics

ACT-A’s 2021–2022 Strategic Plan & Budget states, “Reflecting its original mandate, … the ACT-Accelerator is shifting its primary aim from being the global solution for equitable allocation of COVID-19 tools to addressing inequities in access to COVID-19 tools.”22 This can be construed as a shift away from the idea of donors taking the lead in equitably distributing goods such as vaccine and tests, to an idea that places the people of low- and middle-income countries at the center and pursues fairness by supporting their access to healthcare. To realize this shift, the key will be factors other than the supply of goods, including ACT-A governance reform, the strengthening of health systems, and technology transfers, and this will not be possible without bottom-up reforms that start with listening closely to health workers on the frontlines of primary healthcare (PHC).

The Strategic Plan & Budget proposes that indicators should be developed to capture the downstream logistics near the frontlines of healthcare to emphasize support for in-country uptake and that HSRC should take on the role of tracking bottlenecks and coordinating among multiple sectors. According to the COVAX vaccine forecast, the vaccine supply will reach a level high enough to cover more than 30 percent of the population of AMC countries by around March 2022.23 This shows that the bottleneck is shifting from supply to allocation and deployment,24 which means that securing sufficient health system capacity will be essential to address the bottleneck. In addition, the sharing of epidemiological data among stakeholders is critical in order to prepare for a pandemic, and healthcare workers and community health workers at the frontlines of community PHC often serve an integral role in on-the-ground surveillance and other tasks that provide the basis for that epidemiological data.25 As for the procurement of pharmaceutical products, although not without their own challenges, existing mechanisms such as the Pooled Procurement Mechanism, a Global Fund initiative for joint procurement, are recognized as having contributed to mitigating the disruption of the pharmaceutical supply network caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.26 These reflections suggest that pandemic response is not about strengthening something specific to the situation, rather they seem to highlight the importance of ensuring continuity with the essential healthcare services and the mechanism to provide those services at normal times. Strengthening PHC is integral to promote universal health coverage (UHC), and a robust health system forms the basis for pandemic response.27 On the other hand, although the “Major HSRC milestones over the next 12 months” listed on page 24 of the Strategic Plan & Budget are pointing in the right directions, they seem to be based on the assumption that the government and health systems of each country have a certain level of capacity and that donors are cooperating well with each other. For fragile countries that do not even have the sufficient components—infrastructure, human resources, and a functioning governance system— required to provide PHC, however, those assumptions are hard to meet. In addition to taking a country-based perspective, support needs to be designed mindful of the disparities in the social determinants of health within the country, and to provide support such as proportionate universalism that considers more vulnerable regions and populations while responding to society as a whole.28 In particular, bilateral assistance is difficult to provide in regions that are unstable due to conflicts or coups, and therefore NGOs and multilateral frameworks like ACTA are needed to play that role instead.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic was not limited to the spread of COVID-19 itself. We must not overlook how the overwhelming strain on and collapse of healthcare services in general had a significant impact on existing efforts to address infectious disease and maternal and child health, particularly in low- and middle-income countries.29 It is necessary to strengthen PHC so that we can ensure the continuity of essential healthcare services even during times of health crises and maintain our progress toward UHC.30 Today, in this globalized world, if even one person is at risk of infection, then everyone is at risk, or in other words, “No one is safe until everyone is safe.” The same underlying idea can be found in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) pledge to “leave no one behind.”31 Transparent and inclusive collaboration with diverse stakeholders is indispensable to reflect voices not only from the public sector but also from the grassroots, including NGOs/CSOs, the community, the private sector, and other actors who are familiar with the circumstances of the local area. We must realize detailed and well-tailored support in order to achieve UHC for the “human security” of each and every person living there.32

About the Author

Kentaro Nishimoto is a Professor at the Graduate School of Law at Tohoku University.

Disclosure of Conflict of Interest

The author of this paper is affiliated with the Japan Center for International Exchange (JCIE), which receives grants from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, a co-convening partner of ACT-A. JCIE also operates a special initiative, Friends of the Global Fund, Japan (FGFJ), which advocates for ending epidemics of HIV, Tuberculosis, and Malaria through Japan’s investment in the Global Fund, another co-convening partner of ACT-A.

The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of JCIE.

Notes

- For more on the background of the establishment of ACT-A and its structure, see WHO, “ACTAccelerator: Status Report & Plan, September 2020–December 2021,” https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/act-accelerator-status-report-and-plan

- Dalberg Advisors, ACT-Accelerator Strategic Review, WHO website, October 8, 2021, https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/act-accelerator-strategic-review, 3. For a summary of its recommendations. see Dalberg Advisors, “ACT-Accelerator Rapid Strategic Review” (presentation at the 7th Access to COVID-19 Tools (ACT) Accelerator Facilitation Council meeting, October 15, 2021), https://www.who.int/newsroom/events/detail/2021/10/15/default-calendar/7th-access-to-covid-19-tools-(act)-acceleratorfacilitation-council-meeting.

- Alexandra L. Phelan, et al., “Legal Agreements: Barriers and Enablers to Global Equitable COVID-19 Vaccine Access,” Lancet 396, no. 10254 (2020): 800–2, doi:10.1016/S0140- 6736(20)31873-0.

- AVAT, Africa CDC, and COVAX, “Joint Statement on Dose Donations of COVID-19 Vaccines to African Countries,” November 29, 2021, https://www.who.int/news/item/29-11-2021-jointstatement-on-dose-donations-of-covid-19-vaccines-to-african-countries.

- FIND, “SARS-COV-2 Test Tracker,” https://www.finddx.org/covid-19/test-tracker/.

- Dalberg Advisors, ACT-Accelerator Strategic Review, 14.

- WHO Regional Office for Africa, “Six in Seven COVID-19 Infections Go Undetected in Africa,” October 14, 2021, https://www.afro.who.int/news/six-seven-covid-19-infections-go-undetectedafrica.

- Carolina Batista, et al., “The Silent and Dangerous Inequity around Access to COVID-19 Testing: A Call to Action,” EClinicalMedicine 43 (2022): 101230, doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101230.

- Dalberg Advisors, ACT-Accelerator Strategic Review.

- Francesco Guarascio, “Dozens of Firms to Make Cheap Version of Merck COVID Pill for Poorer Nations,” Reuters, January 21, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcarepharmaceuticals/merck-covid-pill-molnupiravir-be-produced-by-27-drugmakers-2022-01-20/.

- MSF Access Campaign, Médecins Sans Frontières, “License between Merck and Medicines Patent Pool for Global Production of Promising New COVID-19 Drug Molnupiravir Disappoints in its Access Limitations,” October 27, 2021, https://msfaccess.org/license-between-merck-andmedicines-patent-pool-global-production-promising-new-covid-19-drug.

- WHO, “ACT-Accelerator Strategic Plan & Budget, October 2021 to September 2022,” https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/act-accelerator-strategic-plan-budget-october-2021-toseptember-2022, 22.

- Dalberg Advisors, ACT-Accelerator Strategic Review, 26, 27, 31, 67, and 68.

- See the following statements from the Platform for ACT-A Civil Society & Community Representatives, available on the COVID-19 Advocacy website: “Statement on the ACT-Accelerator Strategic Review,” 12 October 2021, http://covid19advocacy.org/wpcontent/uploads/2021/10/Statement-on-the-ACT-Accelerator-Strategic-Review-12-October-2021.pdf; “Key Issues to be Addressed in the Updated ACT-A Strategy,” October 2021, http://covid19advocacy.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Letter-to-ACT-A-Facilitation-CouncilOctober-2021.pdf; and “HSRC Strategy Update and Civil Society Participation,” October 27, 2021, http://covid19advocacy.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/CS-Letter_HSRC-Strategy_28Oct2021.pdf

- Dalberg Advisors, ACT-Accelerator Strategic Review, 32–50.

- Suerie Moon, et al., “Governing the Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator: Towards Greater Participation, Transparency, and Accountability,” Lancet 399, no. 10323 (2022): 487-–94. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02344-8.

- Katerini Tagmatarchi Storeng, et al., “COVAX and the Rise of the ‘Super Public Private Partnership’ for Global Health,” Global Public Health (October 22, 2021): 1–17, doi:10.1080/17441692.2021.1987502.

- Kim Robin van Daalen, et al., “Symptoms of a Broken System: The Gender Gaps in COVID-19 Decision-Making,” BMJ Global Health 5, no. 10 (2020): e003549, doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003549.

- ACT Accelerator. “New ACT-Accelerator Strategy Calls for US$ 23.4 billion International Investment to Solve Inequities in Global Access to COVID-19 Vaccines, Tests & Treatments,” WHO, October 28, 2021, https://www.who.int/news/item/28-10-2021-new-act-accelerator-strategycalls-investment

- Global COVID-19 Access Tracker, https://www.covid19globaltracker.org/.

- Dalberg Advisors, ACT-Accelerator Strategic Review, 56.

- WHO, “ACT-Accelerator Strategic Plan & Budget, October 2021 to September 2022,” xiii and 5

- COVAX, “COVAX Global Supply Forecast,” COVAX Facility and COVAX AMC Document Library, December 14, 2021, https://www.gavi.org/sites/default/files/covid/covax/COVAX-SupplyForecast.pdf.

- COVAX, “BREAK COVID NOW, The Gavi COVAX AMC Investment Opportunity,” COVAX Facility and COVAX AMC Document Library, January 28, 2022, https://www.gavi.org/sites/default/files/covid/covax/Gavi-COVAX-AMC-2022-IO.pdf.

- Matthew R. Boyce and Rebecca Katz, “Community Health Workers and Pandemic Preparedness: Current and Prospective Roles,” Frontiers in Public Health 7, no. 62 (March 26, 2019), doi:10.3389/fpubh.2019.00062; FBM Maciel et al., “Community Health Workers: Reflections on the Health Work Process in COVID-19 Pandemic Times,” Cien Saude Colet. (October 25, 2020; suppl 2): 4185-–95 (Portuguese, English), doi: 10.1590/1413-812320202510.2.28102020.

- The Global Fund, Office of the Inspector General, “Procurement and Supply Chain during the COVID-19 Pandemic,” December 6, 2021, https://www.theglobalfund.org/en/oig/updates/2021-12- 06-audit-of-procurement-and-supply-chain-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/.

- World Bank, “Walking the Talk: Reimagining Primary Health Care After COVID-19,” World Bank, June 28, 2021, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/35842 ; WHO, “Universal Health Coverage Means a Fairer, Healthier World for All,” December 10, 2021, https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/universal-health-coverage-means-afairer-healthier-world-for-all.

- D Graham Mackenzie, “Using Key Concepts from the Marmot Review to Frame COVID-19 Response,” BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 372, no. 795 (March 22, 2021), doi:10.1136/bmj.n795.

- Global Financing Facility, “Emerging Data Estimates that for Each COVID-19 Death, More than Two Women and Children Have Lost their Lives as a Result of Disruptions to Health Systems Since the Start of the Pandemic,” September 29, 2021, https://www.globalfinancingfacility.org/emergingdata-estimates-each-covid-19-death-more-two-women-and-children-have-lost-their-lives-result. WHO, “Third round of the global pulse survey on continuity of essential health services during the COVID-19 pandemic: November–December 2021, Interim report” February 7, 2022, https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-EHS_continuity-survey-2022.1

- United Nations, “Policy Brief: COVID-19 and Universal Health Coverage,” October 2020, https://unsdg.un.org/resources/policy-brief-covid-19-and-universal-health-coverage.

- ACT Accelerator, “Commitment & Call to Action,” April 24, 2020, https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/access-to-covid-19-tools-(act)-acceleratorcall-to-action-24april2020.pdf.

- For further details on human security and health threats to human security, see UNDP, Special Report 2022: New Threats to Human Security in the Anthropocene—Demanding Greater Solidarity (February 8, 2022), https://hdr.undp.org/en/2022-human-security-report .